Practically everyone knows health care in the United States is expensive — the most expensive in the world by seemingly every measure. But judging by the raging debate over the Affordable Care Act, few really understand why.

Practically everyone knows health care in the United States is expensive — the most expensive in the world by seemingly every measure. But judging by the raging debate over the Affordable Care Act, few really understand why.

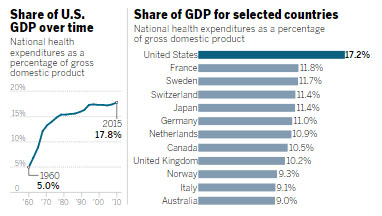

At the moment, the GOP-led push in Congress and the White House to overhaul Obamacare is focusing on premiums and deductibles, coverage rates and co-pays. Yet they are just the mechanisms of paying for a system that continues to consume a larger percentage of the nation’s gross domestic product than in any other highly industrialized country. For example, a study from the Commonwealth Fund, a nonpartisan health-care think tank, said the United States spent $9,086 per person in 2013 on medical expenses — $2,761 more than Switzerland, the next-highest spender on the list of 13 wealthy nations.

Despite this big spending gap, the United States’ overall life expectancy was only 78.8 years in 2013, the lowest among its peers. It also had the highest infant mortality rate and obesity rate in the group, according to the study.So if Americans are not getting better results, then why is our health care so costly? The experts give resoundingly similar conclusions.

“When you do the research, you realize it’s really not because we’re using more care. It is that we have these higher prices that we don’t see in other countries,” said David Squires, a senior researcher at the Commonwealth Fund.

“The biggest reason is that we have higher prices for health-care services in the U.S. than other countries have,” said Cynthia Cox, associate director of the Program for the Study of Health Reform and Private Insurance at the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation.

“We pay our doctors more, we pay our hospitals more, we pay more for our drugs,” said Geoffrey Joyce, a health-care economist with the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

The Commonwealth study found that among industrialized nations, there were significant pricing differences for many medical procedures. An MRI scan in the U.S. cost $1,145 on average in 2013, compared with $138 in Switzerland, $350 in Australia and $461 in the Netherlands. An appendectomy cost $6,645 in New Zealand and $13,910 in America.

The U.S. has experimented with many ways to reduce skyrocketing medical costs, including moving to the health management organization model — HMOS — in the 1980s and ’90s and, more recently under Obamacare, to systems that allow health providers to keep part of the money they save as long as the quality of patient care remains high.

There are recent signs that some of these efforts are bearing fruit. After decades of steady increases, the amount of GDP consumed by health-care services has flattened in recent years.

However, American drug companies, health providers and patients themselves are still largely unwilling to give up control over myriad medical choices — a relinquishment that has been crucial for governments in other countries to hold down costs more effectively.

Health-care specialists cite several key reasons why Americans are shelling out more money for what’s often less quality:

Price variations

Need a knee replacement? That will cost you a different price depending on where you go in the United States.

A California website shows that hospitals in San Diego County charged anywhere from $52,010 to $98,327 for the procedure in 2014, but that’s just the list price. Each hospital brokers its own deal with each insurance company. The public never really gets a full picture of what insurance companies pay behind the scenes, though the amount of information available is gradually increasing.

Medicare, on the other hand, has a much more standardized pricing structure that attempts to pay based on a person’s severity of illness, the cost of living in each geographic location and other factors.

America’s system of variable and relatively opaque pricing does not exist in other countries, said Squires at the Commonwealth Fund. Government-run “single payer” systems, even those with several insurance companies participating, get much more involved in setting prices for everything from prescription drugs to individual medical procedures.

“In other countries that have more centralized prices, those sorts of price disparities don’t really occur,” Squires said.

Such systems also wield much greater control over what kinds of medical procedures, medications and therapies are available to consumers. They conduct cost-effectiveness reviews to decide if a given service is worth the investment of limited health-care dollars, said Cox at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The United States has resisted all attempts to adopt a similar approach.

For example: The Affordable Care Act originally called for a panel to conduct effectiveness research, but that provision was quickly scrapped when some legislators said cost-benefit analyses would result in “death panels” that denied care to people whose lives were not deemed valuable enough to justify the medical expense.

Meanwhile, many free-market thinkers such as Dr. Michael Accad, a San Francisco cardiologist who runs a blog called Alert & Oriented, believe excessive regulation is to blame. They note that consumers, if given enough accurate pricing information, are capable of finding the best combination of price and quality. They said insurance coverage — with its complicated mix of premiums, co-pays, deductibles and co-insurance — only drives up costs by obscuring the true pricing dynamics.

“When health insurance pays for medical care, the demand for health-care services, medical technology, drugs and so forth is bound to go up, and this naturally pushes prices up by the law of supply and demand,” Accad said.

Like some physicians, he treats only cash-paying patients and posts his prices on his website for everyone to see.

Prescription drugs

Studies have repeatedly made it clear that Americans pay more for prescription drugs than people in other countries.

The International Federation of Health Plans compiles an annual list of drug prices by country. According to that comparison in 2015, the rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira cost $2,515 to $2,996 in the U.S., $1,362 in the United Kingdom and $552 in South Africa. The painkiller OxyContin cost an average of $265 in the U.S. that year, versus $95 in Switzerland.

“Pharmaceutical prices are very easy to compare, and we can see very clearly that we pay two, three or even four times as much, in many cases, for the exact same pill,” Cox said.

Countries with centralized health systems have an advantage in this regard as well, she noted. They are able to negotiate for an entire nation all at once, in contrast to individual insurance companies or government programs working out their own narrower deals.

“We have more of a fractured purchasing system, and as a result, we don’t have the same negotiating power,” Cox said.

Here again, Accad sees the current health insurance system, which offers prepaid drug benefits rolled up in the premiums that consumers pay, as the real problem. Just as the market has convinced some doctors to offer their services on a cash-only basis, some consumers are buying their medications on the Internet from sellers in countries charging lower prices.

“Things are so bad that the market is finding ways to circumvent the (U.S.) system and get people what they need at a price they can afford,” Accad said.

Technology

American health care generally uses more high-tech devices than other well-off countries’ medical systems.

The Commonwealth Fund’s report said the United States has 35.5 MRI machines and 43.5 CT X-ray scanners per one million residents. Among the 13 other industrialized nations analyzed, the median numbers were 11.4 MRI machines and 17.6 CT scanners. Only Japan showed a greater investment in these two technologies.

In addition, Americans underwent more scans with such machinery than in most other industrialized countries. And yet their medical outcomes were not superior to those of people in those other nations.

Likewise, studies have shown that within the U.S., hospitals that order noticeably more scans generally do not have better patient results than hospitals that prescribe fewer scans.

Joyce, the USC health-care economist, said technology is a major driver of medical-pricing inflation in the United States. He described an interplay between technology and insurance that, over time, has driven up premiums as never-ending demand for the latest gadgets continues.

On one hand, this pattern creates an incentive to invent and bring new technologies to market. “Clearly, technology wouldn’t be developed at the pace and wouldn’t be able to command the price if insurance costs were not increasing to meet those prices,” Joyce said.

But a lack of centralized pricing control in the U.S. means that access to new technologies is rationed with the pocketbook instead.

“Everybody rations access to these technologies. In European countries, they do it on the supply side by deciding what they’re going to buy and how much. In the U.S., we typically ration based on income and ability to pay,” Joyce said.

Doctors’ compensation

A major focus of health reform in the United States has been changing the financial incentives for doctors, and many health-care economists said this push has helped contribute to the recent plateau in America’s overall health-care costs.

Joyce said provisions in the Affordable Care Act that compelled both health providers and insurance companies to concentrate on the financial value of care, rather than pure volume of care, have made a significant difference.

“The (Great Recession) did contribute some to the plateau we’re seeing in the growth of health care costs, but moving away from the fee-for-service model of incentives is a big deal. We have a long way to go still, but I think you can say it has helped,” he said.

In the past, insurance companies and government programs paid per medical procedure, which encouraged doctors to do more procedures so they could collect more money. Now, the strategy is to increasingly pay one flat fee for an overall case — say, all services related to a brain surgery, from preparation work before the operation to post-surgical radiation and physical therapy.

Experts have said the traditional compensation approach also has contributed to physicians ordering more tests, scans and other unnecessary services to shield themselves from complaints of malpractice. The concept, often called “defensive medicine,” holds that doctors are less exposed to lawsuits if they can show that they had provided a lot of care to a patient.

Waste and fraud

A 2012 report from the Institute of Medicine estimated that the U.S. health system wastes about $750 billion per year.

Unnecessary services made up the largest category of waste. Other major segments were excess administrative costs and an over-abundance of efforts to document care given to patients.

Fraud — even though it tends to grab the public’s attention because of high-profile prosecutions of such criminals — was one of the least significant categories of waste, according to the institute.

The Affordable Care Act has had mixed results in reducing these costs.

A massive move toward computerized record-keeping for medical centers was supposed to achieve greater efficiency and thus lower expenses, but that campaign remains fragmented, said Cox at the Kaiser Family Foundation. For instance, systems designed and installed by different vendors still don’t communicate with each other as they should.

Source:

http://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/news/health/sd-me-healthcare-costs-20170318-story.html

Speak Your Mind